We Must Believe Our Problem Will Wane

By L. G. Merrick

Illustrated by Steve Morris

The pandemic was done, it seemed. The country had reopened. Time to celebrate. We rented a cabin in the woods. Me and Chrysalis. We rented a car for the trip too, rather than use our own, to make everything feel new. We needed it.

“I’m upgrading you to a Volkswagen Passat,” said the guy at Avis. “It hasn’t gone anywhere in a year.”

“Us neither,” I said.

Chrys leaned across the counter to tell the guy, “We moved in together and then—surprise—one week later, shelter in place started. Can you imagine? We barely knew each other.”

I had forgotten her habit of springing personal info on strangers.

Above his light blue orderly’s mask, the guy’s eyes became a billboard of uncertainty. “But you survived it,” he said.

“Barely!” she said. “I thought I would kill him.”

The guy laughed. He didn’t know it wasn’t funny.

● ● ●

Four days later, when we pulled into Avis to return the car, Chrys was laughing. She sounded genuinely relaxed. I’d begun to like that sound. She’d relearned it over those four days. I hoped it would stick even when we got back into the claustrophobia of our apartment.

She went in to use the restroom. I opened all four doors and the trunk to search for an earring. I wanted to be the hero. She’d spent the third day upending the cabin in search of her lost earring, fretting, snapping, tension creeping back into her voice, all our progress teetering—before finally she gave up. But on the drive home I’d secretly gotten the idea that maybe the earring was in the car. There was a lot of litter on the backseat floor because we snacked as we drove and dropped the wrappers behind us. That was hard for me. I hate a mess, but I had to make an effort to relax too, it was only fair, so I helped make a mess, and it made her happy to see me do it. Which was the goal. The goal of everything.

I pushed the wrappers around, reached under the driver seat. Felt through the carpeting, along the stiff edges where it was cut away so that the seat could be bolted into place. Lowered my head to the rear floor to look under the seat. The fibers scratched at my ear, my hair brushed floor where strangers’ shoes had been. Whatever previous car-renters had stepped in. Whatever might linger for a year. Fester. My face was in it now. I can be painfully aware of germs, filth. But I wanted to be a hero.

I repeated this on the passenger side. My face felt hot. I would definitely wash up thoroughly when we got home—but it was worth it if the earring bought us more happiness. I felt along the cool metal rail the seat slid on.

My fingers came back smeared with brown jelly. Half caramel, half earwax. Grease. I tried to wipe it off on a piece of litter. My eyes and nose itched with rug fibers. The gloop would not rub off. Not completely. I could see it in my knuckles, the follicles, I could feel it.

“All set,” said a guy with a tablet, startling me.

He had inspected the car while I was on my knees digging. I signed.

“Oh hey,” he said. “Is that your earring?”

It lay on the rear floor. A pearl. Gray-white and just about glowing, like a tiny moon. Evidently exposed when I picked up litter to clean my fingers.

Chrys was indeed happy. But I ruined that a little by saying, “Promise you’ll wash it thoroughly before you put it in.”

● ● ●

Twenty years before, I’d been to the lake where the cabin was. This time, I felt sad to discover the water level so low, ugly rocks exposed. But I didn’t say so to her. Don’t introduce negativity. Pretend the world is sparkling with promise. Halt the compulsion to speak unnecessarily.

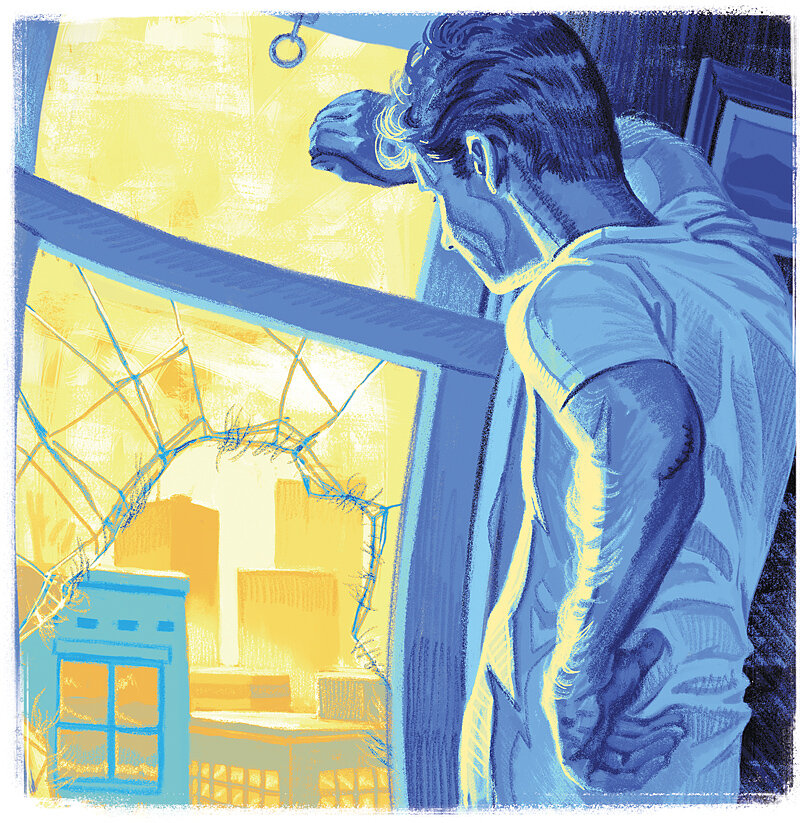

It had been a long year in a tiny apartment. Me working at my computer in the one room that served as both bedroom and living room, her working from her laptop at the kitchen table. I’d come out and ask if she wanted me to make us lunch and she wouldn’t look up from her screen. Would scowl as if I was trespassing. I’d discover she’d already made a sandwich, piled dishes in the sink—or puddled water all over the countertop. She could make a shocking mess rinsing one plate. It was because she was impatient. So I would say something about making an effort next time. She would abruptly unplug her computer and march out with it, sit on the couch for as long as I was in the kitchen. This might turn into four days of not speaking. Of waking up and wondering if she hated me. If I hated her. I wanted us to work out. Maybe it was nothing personal, she just wasn’t cut out to be so near another person every hour. I wanted us to have a normal life. We would work out if only we had a normal life.

She looked so happy in the woods. Tilting her face to the sun beside the lake. Taking deep breaths of mountain air. We saw strangers’ faces for the first time, no masks, all up and down the village street. We sat inside restaurants. We felt the enormity of rejoining civilization. It felt great. It felt fragile.

When she was still happy our first night back in town, I started to relax. She was happy, so we were happy.

● ● ●

The infection filled her earlobe first. The flesh around her piercing turned red and the bottom of the lobe swelled to a dangling bulb.

“It’s numb,” she said.

She swabbed the hole with saltwater again.

“I cleaned the post before I wore it,” she said.

I didn’t mention how hard I’d scrubbed to get the grease off my fingers. Steaming water, Boraxo, three complete tries that turned my hands red. If any of that gunk was on the post, a tissue dipped in saltwater didn’t do anything. I didn’t say this.

In the night she tossed and moaned. In the morning we went to urgent care in a strip mall. The red swelling had spread. That whole side of her head glowed hot pink. The other side had faded to a pallor. We sat in the waiting lounge with bleeding people.

“My cheek is tingly,” she said. “My brain, maybe.”

The ear had gone dark red. Nearly brown. Tough-looking, thick, rubbery. By the time her name was called, her ear had stretched out, enlarged.

“It hurts but actually I can hear better,” she told the doctor. “Like my ear canal is stretched wider to let more sound in. I hear everything so much, it’s giving me a headache.”

He was white-haired and made me think of a guy accustomed to retirement who had come out of it to pay some unforeseen bill. Like a store greeter but with a stethoscope. He looked confused until he wrote a prescription, and that made him happy.

“Here. This will fix it for sure. Come back in 24 hours if there’s no improvement.”

That night the enlarging brown ear, we noticed, formed a point at the top. It sprouted a lot of hair too. Tufts along the edge and back. A bush of downy hair inside.

“It’s getting better,” I told her.

I am not a good liar. She looked in a mirror and cried. Neither of us slept well. I woke up and used a flashlight to look at her ear. It had gotten even pointier. The infection had spread to the other ear and that was starting to enlarge too.

In the morning she had a snout. Her nose had elongated to form it. Upper lip had pulled up into the tip of her nose. Her jaws had extended outward. The expansion had put gaps between her teeth.

Hair sprouted from her cheeks too, and her neck. Thin but unmistakable. Brown like her normal hair. She took off her shirt in the bathroom.

“Stay out,” she said.

Respectfully, I listened to her crying through the door. I was completely supportive. I did exactly what she asked. I was part of the solution, not the problem.

“The penicillin isn’t working,” she said.

She came out with her shirt back on. Eyes red, dilated. Her widow’s peak had crept down an inch. The hair on top of her head was thicker than ever.

“Does it hurt?” I asked.

“I feel weird. Like too much caffeine and chocolate. Like I want to do a million things but I’m queasy and I might fly apart, so I can’t do any of them,” she said. “My knees hurt.”

Her knees looked okay.

“We better go back to the urgent care,” I said.

“I don’t want to be seen, sitting there,” she said. “It’s embarrassing.”

“I bet they take you right away.”

They did not take her right away.

“How many weeks has this been developing?” the doctor asked.

It was a different doctor. A woman who told us we were liars.

“For one thing, hair can’t grow as fast as you’re telling me,” she said.

“Does that mean I should be observed overnight?” Chrys asked.

The doctor said, “No,” sharply, and eyed me as if I might be concealing a camera, to shoot some kind of prank video.

“There are people with real problems,” she said. “It puts them at risk, that I can’t spend my time looking at them because you’re in here making a big show of whatever this is.”

Chrys cried in the car ride home.

“I look like a dog,” she said.

“Everybody loves dogs,” I said.

It was the wrong thing to say.

That night was the roughest yet, and the next morning we woke to find her knees had reversed. Her legs definitely did resemble the rear legs of a dog. Her heels didn’t touch the floor. Her feet were much longer than normal. She had a bouncing walk on her toes. Her breastbone jutted outward now, between her breasts, which had flattened. Her shoulders had pushed in. Her hips had become sleek flanks. So she was thinner, if you looked at her straight on. But in profile she was bigger, hunched forward, aggressive. With every step she seemed to be leaping forward, as she paced the apartment. She was so hairy that she looked ridiculous in clothes.

“No leave,” she said. “No tell.”

She couldn’t really talk.

“You mean let’s stay in?” I asked. “You don’t want to tell anyone this is you?”

She nodded sadly.

“Does it hurt?”

“Teef,” she said.

New teeth were coming in, breaking through the gums in the spaces between her old teeth. Edged, triangular, meat-ripping teeth. Her old teeth looked more cutting now too.

“Do you want an Advil?” I asked. I looked in the cabinet. “I mean Bufferin. We have Bufferin.”

She took two and lapped water from the glass and we curled up on the couch with the TV on.

“Our reintegration into society has hit a speed bump,” I said.

She gnawed on my hand. It helped her teeth feel better.

“Ow,” I said.

She’d broken the skin.

“Shrr,” she said.

She meant “Sorry.”

“That’s okay,” I said, stroking the back of her neck with my other hand, the one not in her mouth. Her coat had become luxurious.

I felt nervous though. Panicked. It was all I could think about. Infection. After two minutes I couldn’t take it anymore. I pretended I needed to pee. Then in the bathroom I rinsed the bite with rubbing alcohol. That stung—bad. But I wanted more sting. I wanted to feel germ-killing sting deep. I wanted it to run up a vein past my elbow. Into my heart. Stop whatever virus she had, whatever was probably in her saliva, in her bite, in my hand, in my blood now. I could not turn into a dog too.

If I did, how would we pay the bills? She had not been able to use her keyboard all day. Her fingers had fattened and turned padlike, she hadn’t put in any hours at work.

The next morning, when I looked into her face, I didn’t see any humanity anymore. She was not a dog though. She was a wolf.

She paced the apartment on all fours like it was a cage. Her front paws were massive, with dark curved nails. As if feverish or wild she knocked over a chair. Her tongue was bright pink and long. Her look was restless, hungry.

I felt afraid. I couldn’t go near the things she had knocked over.

When she reared up, I tried to be cool. Those forelegs were more apelike than canine. I could still see the primate in her—if I concentrated on not freaking out. I could clean up the mess later.

“Good girl,” I said carefully.

Heart thundering, I went to the store. I bought six steaks, a sack of Purina Puppy Chow, and a red plastic net full of oranges. She’d been looking at me in a way I’d never seen before on any animal but that was unmistakable. Looking at me like she knew she could be a lot happier if she could forget, for just one minute, who I was. Forget just long enough to put those jaws around my neck, and tear.

The steaks were a hit. Raw. She ate the first one slowly, but once they’d warmed up to room temperature she ate the next three as quickly as she used to eat potato chips.

By the last one she seemed bored with steaks. She dragged it around, dropped it, threw it with a shake of her head, looked at me, looked out the windows.

She wanted out. That seemed bad.

The Puppy Chow and oranges were of zero interest. I had been hoping that the oranges in particular would be a hit.

We didn’t sleep in the same bed that night. I let her use it. I slept in my old Civic in the parking garage. Before I went to sleep, I poured floor cleaner in a circle around the car. I wanted the ammonia stink to make it impossible to follow my scent.

It was hard to sleep. What are we up against, I wondered. Should I buy a gun? Make silver bullets? I googled moon phases on my phone. It was time to consider the possibility her condition was moon-related. Google revealed tonight was the full moon. Yesterday had been a slice less, tomorrow would be a slice less again. Tonight was the worst it could get. If it was moon-related.

It’s not so bad, I decided. She does not have a tail.

I latched onto that.

The hand she had bitten tingled, red around the punctures. It felt hot.

How did we get through a year without coronavirus—isolated in our apartment every day to make sure we’d get through—only to contract something worse? And contracted from what, a dirty earring? And the something is—lycanthropy?

Assuming the symptoms start to lift tomorrow. That she is not going to remain this way every day.

Maybe I better call the car rental place and tell them to give that Passat an extreme cleaning. Would they be thorough enough? Maybe I better go to the rental lot under cover of night and set that car on fire. But what if the car wasn’t to blame? Maybe the infection had gotten into her ear from the pillow in the cabin. Did I need to burn down the cabin? The woods? Maybe I should drive Chrys across the country to the CDC in Atlanta, or just to a real hospital, like Cedar-Sinai.

I heard a window break.

I stayed in the car and hoped I’d heard wrong.

But I was sure I was right. My hearing had been getting incredibly clear as I lay in the car. I could hear how busy the street was on the other side of the cinderblocks. I heard a bicyclist on the sidewalk, with a chain in need of greasing. I heard a dryer tumbling in our building’s laundry room, warming shirts with buttons. All my senses were so heightened. The ammonia, which should have been fading, instead grew in my awareness, became an intense burn parked in my sinuses. I regretted spilling it. I wondered if any had splashed on the car and would damage the paint. I removed my T-shirt and wadded it over my nose. I fought an urge to roam the world and correct it, violently, as if doing so would fuel me. I tossed and turned and felt as if everything inside me was tightening, knotting together into a hard dense puzzle that I needed to solve and never would. I developed a splitting headache.

● ● ●

In the morning, Chrys was gone. I noticed my arm hair had thickened in the night.

I taped cardboard over the window she’d smashed to escape.

Then there were the blankets on the floor, the bookcase turned over, chairs askew—it took hours to fix the apartment, and afterward I still felt nervous, did not know what to do with myself. I paced. I straightened pictures that I became hyper-aware were slightly crooked, scrubbed the bathroom. Took dishes out of the cabinets that Chrys had washed inadequately before we went to the cabin and rewashed them.

But that night my arm hair seemed to have thinned back to normal, and I was able to settle, watch some shows. I couldn’t hear the traffic more than was normal.

The next full moon probably would he harder on me. I didn’t feel confident I had beaten the virus. I’d only had it easy because she bit me too late. The infection hadn’t found time to take full root. But over the coming month, it would.

I hoped she would come back. Revert as the moon waned, and feel she had strayed enough. She would need to get her computer, at least.

When I was a kid, I had a cat that ran away. I missed that cat. I would lie awake obsessing, feeling I had no control over anything, not even the closest things. The cat wandered, and it wandered off. It never came back. I can’t go through that again. I need to hold everything together. I need to make sure things stay in order. We’re in love and we just need to live some normal life to prove it. As soon as she comes back.

Two days later, I got a call from a number I did not recognize.

“I don’t know how I got here,” she said. She sounded like she had been crying. Like she had finally made a mess she knew was too big to ignore. “I stole clothes. I had to. So I could approach a stranger to borrow her phone.”

“Tell that stranger thanks,” I said. “You’re okay now. I’ll make sure.”

She was 21.24 miles away. I drove to get her in the Civic. I was so glad, I sang along with my music the whole way.

The end