Bleeding Like Lava, Blue Water Womb

By L. G. Merrick

Illustrated by Steve Morris

1.

Let me give you an idea of what Tasya was like. The whole month after she killed our children, she lay around the house sleeping. That was her reaction. Nap it off.

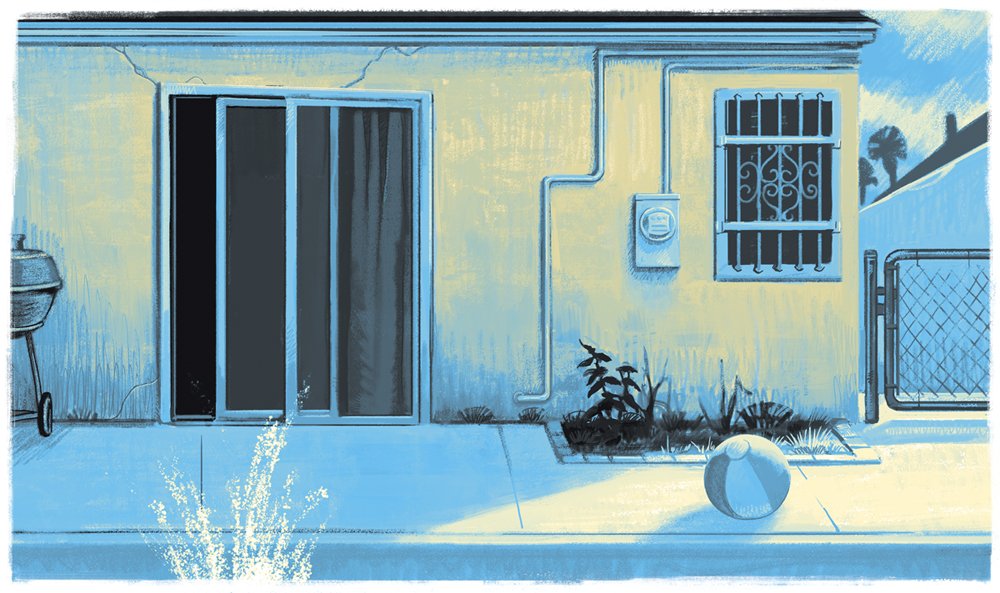

Which was how she killed them too. Asleep on the couch. The sliding glass door wide open.

As for me, in contrast? Where my heart was, there now seethes a volcano. All day and night it erupts.

“You don’t do anything,” I told her. “No job, no housekeeping. You had no right to be tired, no right to nap.”

The police watched the security video. Zara toddled out, the cop told me. Fell into the pool. Adam ran out, jumped in to save her. Brave boy. Helpful. What a man he was going to be. I wanted to meet that man.

Last night, finally Tasya broke her silence. Her monthlong, drooling silence. She broke it into screaming. Woke me up.

And gibbering. She wouldn’t stop raving, middle of the night. Mostly in the primitive, slush-soaked, absurd sounds of Russian, which I don’t speak — but making no more sense even when she mixed in some English.

“They’re still here! Look!” Delusional.

“They’re not, and that’s because of you.”

Eventually she said, “I should go home to Volgograd, never look back!”

“That’s the only intelligent thing you’ve ever said.”

I handed her fifteen grand. Dug her passport out of my safe. Booked her on the next flight. Called a car to take her to LAX.

Adam got to be four. Zara two. I’ll be in pain forever. Where my heart was, this volcano erupts. Lava cascades through me, and scorches every inch it flows across.

She’s lucky I didn’t kill her.

2.

Usually I work twelve hours. Fifteen. Days off are for the unserious. But the morning I woke up to a house without her, I stayed home to savor it.

Made a grilled cheese, poured a Nolet’s and tonic for lunch, and sat on the couch staring out the open glass door at the pool.

Under red sky, the pool glowed a poetic aqua. A wind stirred the surface, a hot wind bringing the perfume of wildfires a hundred miles away. It was those fires that made the sky red. Noon or dinnertime, no way to know in that red. The news showed the fire consuming other homes, whole towns. Counted the dead. The news did not mention how pleasant the odor was. Like a mesquite cookout.

I savored how calmly I walked from the bedroom to the living room while she screamed. She stood at the open glass door, staring at the pool. I slapped her to stop the screaming. You better believe I did.

After lunch I stripped down to my boxers. It was blistering hot. Somehow last night when she was screaming it was cold. I wished it would be now. Poured a second gin. Watched the light from the pool ripple and swarm, teal and yellow on the living room ceiling, the walls. Watched it shimmer like the scales of a fish. What was my life for, now? Those kids had been the center of my every thought in a way I hadn’t even realized until they were gone. The way you don’t realize you’re breathing until it’s hard to do. I thought of the time Zara drew a picture of me for my birthday and she cried as if in terror because she used the wrong crayon for my hair color. Poor inconsolable girl for no reason.

Poured another. It was a deadly foul wind on the water and it smelled pleasant to me. Ash floated in the air. Like a little snow across the red. I couldn’t decide if I was celebrating or torturing myself.

3.

A splash woke me. As if a kid jumped into the pool.

I lay on the couch listening for more. Watched the pool lights play on the ceiling. I was greasy with sweat, felt sure I had discolored the couch. Good. I should drag the thing outside, torch it. Wave the wildfire onto the back patio. Come take it.

The sky was dark but still red. Low smoky clouds, underlit by neighborhood lights weak in the thickened air. My phone said 3:04 a.m.

At another splash, I sat up.

Not long ago, neighborhood kids were jumping the fence to use our pool in the night. Adam was two and Zara still baking. That was why I put in the surveillance camera. It was a game, the police told me. They’d cross the neighborhood, these kids, pool by pool, swim one lap in each. How many pools could they swim before a patio light flipped on, an owner yelled? That was the game. Teens are monsters. No respect. Twice I saw bare backs flop over the fence to get away. Heard them laugh at me as they escaped.

Tasya said, “Who cares.”

I told her, “You’ll care when one of these dope-smokers drowns and we get sued for every cent by his worthless parents.”

That shut her up. A Russian’s one true focus is money. Marry a Russian, you learn that lesson. Land of gangsters and whores.

Tonight I stood at the glass door a long while, waiting to see kids bob up. Kids who’d gone under when they saw me stand. Two kids, three or four, holding their breath. They’d have to come up.

I waited until they had to be dead. There were no kids in the pool.

Maybe Zara ran straight in, not looking. Or maybe she stopped at the edge and reached for a leaf, a bug, a feather, slightly too far. She would pick up anything and carry it around like a doll, like it mattered. Carried a bee around once, cupped in her tiny hands. It didn’t sting her. I told Tasya, “That’s a magical fucking child.” I worried about the day she’d get out into the world and trust it not to sting her.

Picturing Adam was easier. He ran with a bounce, and a side-to-side wobble, always grinning. Everything was an adventure to that kid. Oh Jesus.

Oh Jesus, kill Tasya, Lord, or wake her up and make her live with it.

Suddenly I felt the mist, eddying off the water, crossing the patio, snaking around my legs. What the hell. All day had felt like breathing hot sand. This was like frozen hands. But the change wasn’t a relief. It made me — uneasy.

The door made a satisfying, solid sound as I slid it shut, clicked the latch. The glass was hot. Almost immediately the feeling returned of being surrounded by glowing coals. I took comfort in that.

4.

The next day was Saturday so I only went to the office for six hours. All across the city the air felt tight. My saliva turned to paste. The inside of my nose cracked. The news said the wildfire was thirty miles away, clearing thousands of acres of parkland. When I got home I stripped down to boxers and watched video of cars fleeing down mountain roads. My sweat seeped into the couch. I intended to ruin it.

I had nodded off when another splash woke me. This time I ran to the glass door. It was open. I must have pulled it open. I stepped outside — as if into a refrigerator. How was it so cold?

The water chopped. As if kids had cannonballed in. There was no breeze. I waited for the kids to surface.

I wondered about that game. If it was a local tradition, played for generations. Adam would have learned it someday. He would have laughed up and down at every sucker who didn’t catch him. The time of his life. Maybe I shouldn’t have installed the camera to stop it.

But without the camera — I know what I would have thought.

I would have thought Tasya killed my children on purpose.

I would have pictured her dragging them to the pool by their hair. Wading in. Holding them under. To spite me. To end the marriage. They don’t play right, Russians. They never admit they did anything wrong. They only think they’re capable of love. They love other people the way you love a Rolex, or the BMW M5 — because when strangers see you with those, they believe you must be special. Russians are dead-eyed grifters with an operatic sense of self.

I knew that, as surely as I knew no one had ever been wronged as bad as me. I’m dedicated, I make money — but am I admired like hard work deserves? Those teens thought they were sticking it to some rich jerk. Tasya saw me as a bag of cash. She played the game — find a man twenty years older whose success everyone resents. Be sweet as a cupcake to him — until you squeeze out a kid or two. Then you’ve got a claim on his every individual penny.

I watched my breath. Frosty clouds. My phone said it was 2:47 a.m., 99 Fahrenheit.

Suddenly it hit me: She was having an affair with the cop. The one who said the deaths were accidental. She drowned the kids and that guy lied about the video, then deleted it. She did that because she knows what it means to a man to have children. To send his genes onward, be surrounded by people who respect him, who will remember him after he’s gone. It’s not just the kids she killed. In a way, it’s me.

She probably didn’t get on the flight to Russia. Probably was living with that cop in Simi now, or Glendale, Inglewood, wherever cops live. I went to the surveillance computer for evidence.

I couldn’t click the file though. What if the video was still there, not deleted? I’d see them die. I’d see she did not hold them under. See an accident. I’d hate her less than I did just then. I did not want that. Finger on the mouse, I did not click play.

5.

Tasya called in the middle of the night. At first I thought it was a dream. The call was a minute in before I decided it was real.

“I’m so sorry,” she kept saying. “So sorry.”

I’d been thinking about when Adam told me he wanted to grow up to be a cowboy and fight mummies. Thinking or dreaming. I could see his excited face right there, and then the phone rang and took his face away one more time.

She was crying.

“Don’t ever call me again,” I said.

“Do you see them? Are they there? They’re still in the pool.”

“They’ll never be here, thanks to you,” I said.

“I bought a gun.” She sniffled. “Handgun. Because, moi sladkiy, if they’re truly — I would have to — I don’t know. I’m sorry. Do you understand?”

Gibberish. But she had a pleading tone. She was searching for approval.

“Is the gun in your hand right now?” I said. “Use it on yourself. I want to hear that.”

Her crying rose in pitch. The call went dead. Maybe she hung up. Maybe Russian cell service is crap. Or Glendale service. I prefer to think a bullet ripped through her brain and came out the other side with enough force to blow her phone apart.

6.

Sunday I felt off, so after work I went to church. First time since the funeral. But the sermon was about forgiveness. It was ridiculous, vague. That’s how church is. They never name names. Their number would be up the instant they did. If they said try to forgive Hitler. Forgive that psycho who strangled his girlfriend in the park last month. Forgive your ex. Everyone would abandon the church, if the church ever spelled out what they mean. Church lets you keep your integrity.

At the end of the sermon, someone passed out across the aisle. It did hurt to breathe. The air tasted like smoke. My clothes felt like pins scraping my dry skin.

Back on the couch in boxers, I ordered food and stared out the glass door, with a headache.

Maybe the other night the teens had come back to lob things over the fence, and that was the splashing.

I wouldn’t go look to see what was at the bottom of the pool.

But if they want to play, let’s play. I took the pistol out of the safe. Jesus, Lord? If those kids are against You, send them to me tonight. I will dispatch them to Hell, no problem. Give me a chance to do your work.

7.

Cold shocked me awake as fully as if someone had pressed a bag of ice to my legs. The glass door stood open. Cold air had crept in to the couch. I hit my feet so abruptly that I did not realize the gun was in my hand until I tried to rub the sleep out of my eyes and jabbed the barrel in. Jesus. I stood there in boxers, staring at the shimmering aqua rectangle under the low crimson smoke, in the drifting ash. Shivering.

And I thought maybe not only cold but sound had awakened me. A splash.

I released the safety on the pistol.

Another splash — and a giggle — so I knew for sure. Tonight there was someone in the water.

The giggle rose, turned metallic as it echoed off the concrete, the glass. As it went on it became a hoarse rasp, with a gurgle lurking in it. It doubled into two laughs, in that echo, and became humorless, even inhuman. I listened — and heard exactly what it was. The sound of a kid who laughs to please others. Hopes to. Unhappy laugh, desperate for approval — and dire and empty it rang on.

The disrespect was galling. They were rubbing my face in it. Not trying at all to be quiet. I felt the pistol’s weight and thought of my promise to Jesus, and moved swiftly to the open glass—

I was three steps outside, deep into the cold, before I could halt.

They were in the pool. They gripped the tiled edge, stared up at me. My children. Their expressions suggested they thought maybe they did recognize me. I recognized them, though they were — misshapen. Flesh mottled blueberry. Purpled. Hair wet. Adam’s plastered flat. Zara’s knotted and bunched around her face. Both faces swollen. Loose.

Faintly, their eyes glowed. As if behind the irises, inside, they were silver now.

I couldn’t move.

They laughed again. That was why it sounded like an echo. Two of them.

Awkwardly, they started to come up out of the pool. They struggled.

I should have moved to help them. My children. My own.

But in a moment they flopped over the edge, laughing, onto the concrete patio in a slosh, lay briefly like fish.

“Adam,” I said. “Zara-doll.”

They got to their feet. I stared, unsure what to do. They tottered at me, laughing. Arms outstretched. For hugs. Desperate for hugs.

Closer they came that way. Skin sloughed from shoulders, waterlogged and sunburnt. Babyfat rippled gelatinously under the bunched skin. Zara would not stop smiling, which was true to how she had been in life but now at the force of it her cheeks split, and the smile widened, until it touched her ears. At that her jaw dropped and her tongue worked the air. Her laugh became a shapeless chaotic mewl.

Adam swayed side to side as he approached, voice hoarse, ragged, rising to a screech as if under pressure, as his arms widened, as if he might fall toward me and expected me to catch him.

I shot them both.

The bullets sank in. Small craters in cheese-soft flesh. Shot Adam and Zara, over and over.

Backward I staggered, into the house. Shooting. Kept moving until I fell backward into the couch. If they followed me inside—

I stopped shooting my children. I wanted one bullet left. If they crossed the threshold.

But they’ll never die, I realized as they did indeed enter the house. As they reached for me. They’ll live on. So I will endure — forever.